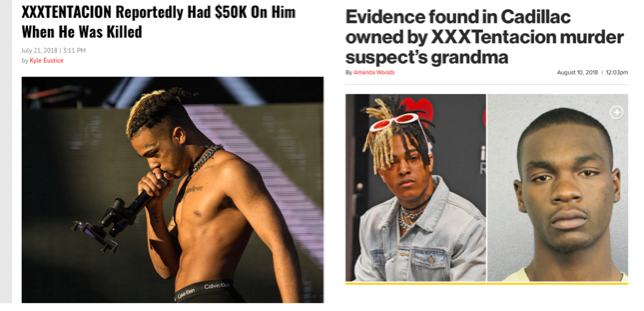

Events surrounding the death of 20-year-old American rapper Janesh Onfroy, also known as Souncloud sensation XXXtentacion, played out in June of this year. Initial reports were focused on Onfroy’s passing (as in the left headline in the above graphic) but as developments in the case continue to receive significant coverage media outlets have begun to concentrate on the investigation of his murder (as in the headline on the right side of the above graphic). Of immediate notice is that the two examples of coverage of Onfroy’s death feature different verb choices with very different consequences.

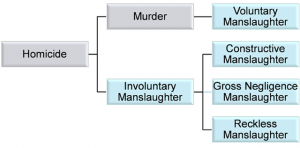

Although the verbs featured in each report are relatively synonymous, they diverge in the passive language of the former (“he was killed”) and the active language in latter (Onfroy is “murdered”). Basic legal distinctions between murder and manslaughter confirm that someone who is killed is not always murdered, with the verbs either revealing or concealing the possible intention for an allegedly responsible party (the “murder suspect” of the second headline).

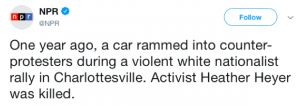

The utility of passive language for precluding the further discussion of a possibly accountable agent is not an observation limited to coverage of Onfroy’s death. Just earlier this week National Public Radio reflected on last year’s violence in Charlottesville, doing so in a similar fashion by stating, “Activist Heather Heyer was killed.” For those unfamiliar with the name, Heyer was protesting a white supremacist rally, taking place in the city, when a vehicle struck her, fatally.

Objects, such as cars, cannot logically be attributed agency in the same way as people, such as those accused or convinced of murder. Yet, in anthropomorphizing the car involved in Heyer’s death through passive language (for it seems as if the car did it on its own), NPR’s tweet strategically avoids using active language to comment on the culpability of any individual, human agent—as was spotted by one Twitter user.

Critical consideration of a word’s function in the construction of a narrative can yield a clearer understanding of the author’s interests in portraying the sequence of events in a particular way—did something just happen, like a lightning strike, or was someone responsible?. If the goal of an article is to galvanize readers into sympathizing with the deceased and attempts to rectify their death, it seems active language would prove much more useful than passive. Thus, it seems logical to assume that coverage with passive language is not primarily concerned with the framing the death as wrongful and following the prosecution of any responsible agents.

How else might our everyday use of language demonstrate significant choices in how we frame events? If, in critically comparing the two descriptions of the same event, we are able to identify consequential shifts in rhetoric that alter the implications of each report then what does this mean for other examples where the stakes are higher? What is garnered or lost when a speaker says they ‘believe’ something instead of ‘think’, or ‘suppose’, or ‘imagine’ it? Should we, as scholars, use a critical comparison of these subtle shifts to identify larger themes they support and the resulting discursive function? For me, given the effects of language clearly demonstrated in the divergent representations of XXXtentacion’s death, it isn’t farfetched to imagine this focus on our words holding value in other contexts with different consequences.